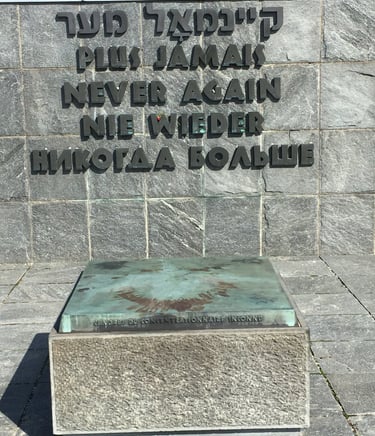

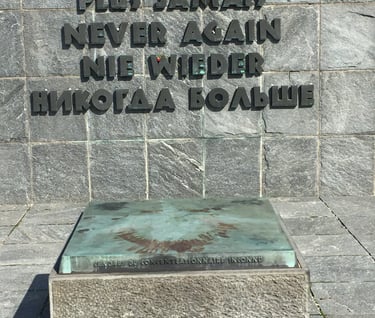

I was on a train returning from Dachau Concentration Camp the day the Syrian refugees arrived in Munich, Germany, in September 2015.

Separated by a single platform, our arrivals could not have been more different.

Having just left Dachau, it struck me how dissimilar the train trips arriving in Germany that day and in the months ahead were from those that delivered millions of individuals to the concentration camps in the 1930s and 1940s.

When hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees, some who had been walking for more than a month, approached the border, I listened as a news reporter asked German Chancellor Angela Merkel if she would “allow” refugees in. Her response was swift and unwavering when she stated Germany would “welcome” the refugees because it was the right thing to do. I am still struck by her linguistic choice, which showed her country’s residents and those around the world that the refugees were not seen as a burden, but as people to be welcomed.

I watched as Munich citizens in the train station cheered and held signs written in Syrian, German, English and Arabic that said, “Welcome to Germany, we are so glad you are here!” When the train doors opened and those completely exhausted refugees stepped onto the platforms, they appeared stunned by what they saw. After reading the signs, I saw their weary faces turn to smiles as they realized that they were not only welcomed, they were wanted. Their harrowing journeys were over.

As the refugees exited the trains, they left on the platforms clean diapers, clothes and blankets given to them by aid agencies as they walked and traveled the more than 1,800 miles from Syria to Germany. Instead of leaving those items on the trains or strewn about, they left them neatly folded and stacked on the platforms for whoever needed them.

A group of three young Syrian men approached me at the ticket kiosk in the station and asked for my help to purchase train tickets from Germany to France. To be clear, they did not ask me for money. They simply asked me whether I could help them navigate the computerized ticket system to find tickets for the most direct route to France. Although they initially asked for my help while speaking German, when they realized that my German was limited to what I remembered from high school, they immediately switched and spoke to me in English. After several minutes, the four of us were able to find the shortest and most economical tickets. As I pointed them to the correct train platform, they thanked me profusely and with tears in their eyes. Mine were filled, too. I will never forget that day.

As nations, we often are called to help others fleeing war-torn countries and atrocities against humanity that we cannot even begin to imagine. Mother Teresa once said, “If we have no peace, it is because we have forgotten that we belong to each other.” As people of mercy and compassion, we must do whatever we can to welcome and help the refugees, immigrants and others in need. Unless one is a Native American, the rest of us sometimes need to be reminded that none of us got here without help from others. The same is true for most things in life. No one gets through this life without needing some kind of help.

While in Germany, I heard stories of incredible acts of kindness toward the refugees that gave me hope in what seemed like a hopeless situation. In addition to assistance from the government and humanitarian agencies, German residents offered rooms in their homes to whoever needed them. When the Austria government closed its borders after a couple of days and refused to let refugees walk across the border into Germany, Austrian citizens formed a convoy of more than 100 cars, picked up refugees who were walking and drove them across the border, where German citizens met them to continue the trip.

The Syrian refugees didn’t know where they were going when they left their war-torn country, what was ahead, if they would survive the journey and, if so, if anyone would welcome them, yet still they came. I often wonder if I would have the same courage and strength to do so if required.

Since that day in 2015, I’ve tried to be more like the refugees in the most basic of ways. I continually work to give away or let go of things I no longer need or want. This includes clothes and other possessions, as well as feelings I stubbornly hang onto, such as loss, uncertainty, fear, hurt and disappointment, even though letting go of them would undoubtedly bring peace to my life. Like the refugees, I try to be grateful for even the smallest kindnesses shown to me, to leave for others what I no longer need or want, and to trust in what I feel is the innate goodness in people.

I’m not always as successful or consistent as I’d like to be, but I intend to continue the journey.

WE BELONG TO EACH OTHER

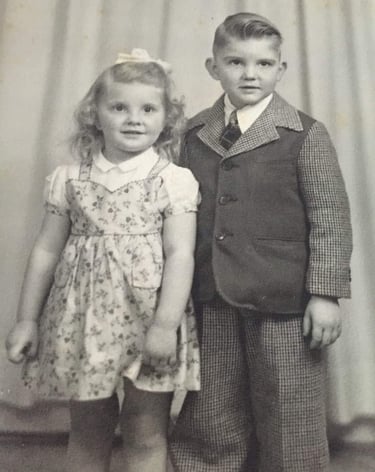

The last year of my Grandpa Becker’s life, I did not exist.

Physically, of course, I was still here, but in his eyes and diminished memory, I was always my mother.

Depending on the visit, he would be visibly anxious as he asked my Dad and I if we remembered to feed the horses that morning, horses they hadn’t had since she was five years old. Most visits, my Grandpa cried when I walked into his room and asked, “Why haven’t you come to see me for such a long time, Lois?” Those visits were the most painful for me because my mother had been dead for three years by then and I was a poor substitute.

Thankfully, the worst day of his life – the day my mother died – he no longer remembered.

My memories of spending time and talking with my Grandpa will last me a lifetime. To say I was a child with a lot of burning questions would be an understatement, but he always took the time to answer them, no matter how ridiculous or impossible they were. Looking back now, I can appreciate and am amazed by his infinite patience with me. Some of the most important things I know today, I learned while sitting in his welding shop or across from him at the kitchen table.

During our visits the last year of his life, my Grandpa’s memories slipped away like sand in an hourglass. Often, we had the same conversations we’d had before, he told me stories I’d heard more than once, and he’d ask questions I’d answered before. Whenever anyone asked me why I still went to see him when he clearly didn’t remember me or when the visits made me so sad, I simply responded, “He may not remember me, but I still remember him. I’ll visit him as long as he’s here.”

By the end of his life, our relationship had come full circle. Growing up, there were many times when I asked him the same questions I had asked him a hundred times before, sometimes to see if there would be a different answer and sometimes hoping that there was because it wasn’t what I wanted to hear. Sometimes I would keep asking, sure that I could wear him down until I got the answer I wanted. Never once did he say, “Are you kidding me, Skinner? Asking me the same thing in a different way is not going to change my answer.” And then I’d ask again.

Memories are curious things. Actions done repeatedly transform into habits that can last a lifetime. I was always amazed that my Grandpa still remembered how to pray the rosary with his black beaded rosary that was worn smooth from decades of use, even when he could not recognize me and other loved ones. It was yet another reminder of how strong his faith was, even when his body and mind were failing.

When my Grandpa thought I was my mother, I never hesitated to respond as though I was her because it calmed him and made him so happy. Somewhere in his fading memory, he was together again with one of the people he loved most. Even if he didn’t know who I was, I wanted that connection with the two of them, too. In the end, all he wanted was to be heard, to be respected, and to be loved by those around him. Such simple needs.

At the end, even though he no longer knew he was still answering my questions and teaching me lessons on how to be a decent human being, he was and that’s one thing I will never forget.

HONORING MEMORIES AND RELATIONSHIPS

LISTENING WITH INTENTIONALITY

I’ve always thought it a beautiful coincidence that the words “listen” and “silent” are spelled with the same letters. For me, it means that to truly listen to another is to do so with intentionality and in silence. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines “listen” as to hear and understand what you’ve heard, and to hear something with thoughtful attention.

To listen to another person requires a deeper, more intimate and sacred act, rather than simply hearing them. There is a distinct difference between hearing and listening.

Hearing is a physical, biological act – one that you do with your ears. In contrast, listening is something you do with your heart. Listening to someone doesn’t mean biding your time until you can jump in with your own solutions, unsolicited advice or opinions. Listening requires patience and complete selflessness. If you are a good listener, it is one of the rare times when you are not the center of attention and, typically, not the subject of the conversation.

My brother Deon died in a car accident on March 19, 2018, when he was 44 years old. The man who completed four Ironman competitions, a 50-mile trail race, and dozens of marathons was gone in an instant. The loss was unimaginable then and sometimes still is today. There are countless things I miss about my brother, but one of the main ones was his gift of listening. Deon and I could drive 500 miles to a race or on vacation and either sing old songs (badly), talk the entire time or not speak more than a dozen sentences.

When one of us wanted to talk about something important, we prefaced it with, “Can I run something by you?” During these conversations, advice was rarely requested and questions from the listener were unnecessary and not expected. The only requirements were that the person listening do so with an open heart and with a feeling of sacredness.

Being asked to listen to another person in this way or to be listened to by another is a gift not to be taken lightly. It comes with great responsibility, vulnerability, trust, love and compassion. There should be no preconceived notions, no need to fill the silence, no pressure to offer solutions, and should be done with a completely non-judgmental attitude.

The act of listening also can be a heavy burden. Sometimes, disassociating oneself from what is being said is used as a protective measure until you can bear to process what you are being told. This happens when learning of the death of a loved one, an unexpected medical diagnosis or the loss of a job. At times like these, although we hear what is being said, it doesn’t register with us because it is simply too painful.

We all need someone in our lives, whether it be a family member, a spouse, a friend or someone else, who is willing to listen when we need to share good news and bad, and to help us process information. That doesn’t mean they need to have solutions for whatever problems we are trying to solve. They just need to be willing to be there. Be that person for someone. Truly listening to another person requires intentionality on your part. You're either all in or you're not listening at all.